Collins's first film, The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy was a 50-minute film based on the work of Henry H. Roth. Although the spritely comedy was a charming and beautifully crafted first-time effort from an indie filmmaker, she was accused of deserting her African-American roots to tell the story of three Puerto Rican brothers scraping by while contending with the ghost of their dead father.

Her brilliant second film, the 1982 comic drama Losing Ground, which she both wrote and directed, centers on the experiences of Sara (Seret Scott), a university professor whose artist husband Victor (Bill Gunn) rents a country house for a month to celebrate a recent museum sale. The couple’s summer idyll becomes complicated as Sara struggles to research the philosophical and religious meaning of ecstatic experience... and to discover it for herself.

When she agrees to appear in a short directed by one of her one of her students, Sara’s search for the “ecstatic moment” and her struggles with Victor’s indiscretions are reflected in the plot of the student film. Performing with Duke (Duane Jones), her charismatic co-star, Sara acts the part of the jealous lover in a film version of the song “Frankie and Johnny.” By the end of shooting, she experiences a moment of profound and shattering emotion that calls her ordered intellectual existence into question. One of the very first fictional features by an African-American woman Losing Ground remains brilliant, stunning, and a powerful work of art.

At a time when black professionals were rarely portrayed in mainstream media, Losing Ground was not released theatrically and only screened once on WNET’s Independent Focusin 1987. Because she was not interested in portraying minorities as victims or thugs, the press and the film industry ignored Collins’s work. The first substantial coverage that Collins received in the New York Times was her obituary.

Accomplished actors Seret Scott (who appeared in Louis Malle’s Pretty Baby and Ntozake Shange’s play ”for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf”), Bill Gunn (Ganja and Hess) and Duane Jones (Night of the Living Dead) star in this story of the emotional awakening of a woman in a troubled marriage. Losing Ground was shot in New York City and in nearby Rockland County, with locations in Nyack, Piermont and Haverstraw.

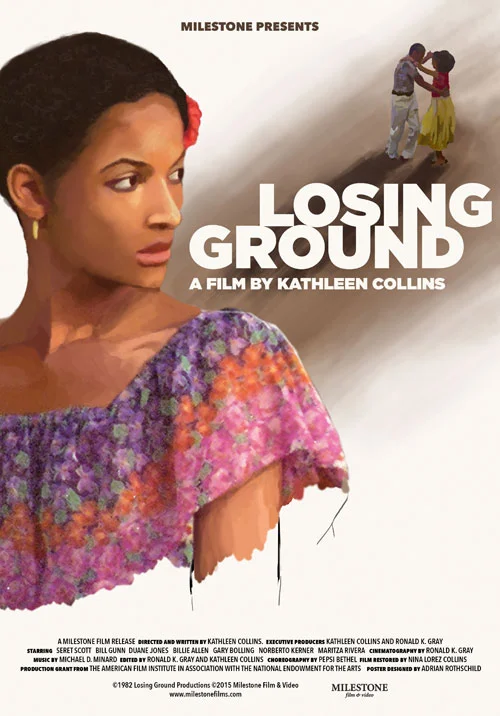

Stills from Losing Ground

While I’m interested in external reality, I am much more concerned with how people resolve their inner dilemma in the face of external reality. How do you resolve it? How do you deal with it? So that’s Sara’s quest for ecstasy is on the external level. But the internal part to her is still a woman raised by a mother who was a little bit libertine and living with a husband who is a little bit too spontaneous... If I favor anything, I probably always favor the internal resolution before the external resolution. Because for me the internal resolution is the most potent in the psyche... You don’t get the resolution, but you get the explosive moment... the final resolution is private choice, even of a character. It’s really none of my business. All I do is take the character to the point where I can see him through the dilemma to the dilemma’s climactic moment. After that, it’s free choice. And not everyone will choose the redemptive path... "

— Interview with David Nicholson, Black Film Review, Winter 1988/89

Among the first fictional features by an African-American woman, Losing Ground was altogether a stunning work by any director. Many who saw it fell in love with the film and its charismatic director. Like Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, a film Collins had greatly admired, Losing Ground’s plot revolved around the lives and relationships of black characters, based on her own experiences, but had universal meaning. In a 1987 interview, Collins spoke about her characters’ evolution:

Essentially it’s that change is a rather volatile process in the human psyche; and, that real change usually requires some release of fantasy energy. This is why it has an element of violence... This is less a feminist statement than it is a statement that any kind of real change or disruption involves some kind of change in the psyche; some kind of fantasy or imagine release before one can actually initiate the change."

— Interview with James Briggs Murray, Black Visions

Losing Ground trailer from Milestone Film & Video on Vimeo.

Losing Ground was first shown in June 1982 at Irvington, NY’s Town Hall Theater, presumably as a “local” premiere. The film’s only New York City screening was on a Monday night on January 24, 1983 as part of the Museum of Modern Art’s Cineprobe series. The New York Times noted the showing with three sentences in their “Going Out Guide.” After that, like many other fine black films — such as Killer of Sheep, Bless There Little Hearts and Bush Mama — there was no interest from the distributors and Collins could only get nontheatrical screenings at a few colleges and film societies. Although greatly admired by her fellow black filmmakers, Losing Ground gained very little notice. And even in the budding age of cable television and the huge hunger for programs, it wasn’t until 1987 that The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy showed on the Learning Channel (when it was a much smaller cable station owned by Appalachian Community Service Newtwork) and Losing Ground screened once on WNET New York’s Independent Focus. One 16mm print of each have been preserved at Indiana University’s Black Film Archive – studied and revered by academics but unseen by the public.

Nina Collins was a teenager when her mother died. Almost 25 years later, she rescued her mother’s original negatives and created beautiful new digital masters so that they now stand as monuments to African-American and women’s cinema as well as testament to Kathleen Collins’ incredible talent.