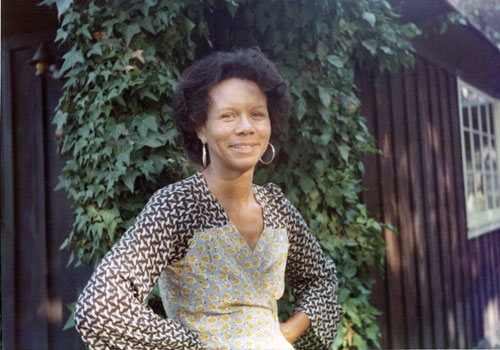

Biography in Brief

Born in 1942, raised in Jersey City, and educated at Skidmore and the Sorbonne, Kathy Collins was an activist with SNCC during the Civil Rights Movement who went on to carve out a career for herself as a playwright and filmmaker during a time when black women were rarely seen in those roles. She was married twice, and had two children who she raised in Piermont, New York. She died young, at age 46, from breast cancer. Her most known work is the film Losing Ground, followed perhaps by two plays, In the Midnight Hour, and The Brothers. A never-before released collection of short fiction, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, will be published by Ecco Press in Fall, 2016.

Extended Biography

Kathleen Conwell Collins Prettyman (March 18, 1942– September 18, 1988) was born to Frank and Loretta Conwell and lived at 357 Pacific Avenue in Jersey City, NJ. Her father worked first as a mortician and later became the principal of a Jersey City K-8 school (now named after him). He later went on to become the first New Jersey African- American state legislator. Her maternal family (her mother’s maiden name was Pierce) came from Gouldtown, NJ, a 300-year-old settlement — still in existence — that started with an interracial marriage and remained a haven for mixed-race marriages through the 20th century.

At fifteen, Conwell won first prize at an annual poetry reading contest at Rutgers Newark College of Arts and Sciences for her rendition of Walt Whitman’s “A Child Goes Forth” and “I Learned My Lesson Complete.” An article in the March 3, 1958 Jersey Journal reported that in addition to working as assistant editor of the Lincoln High School’s publication the Leader, Conwell was on the editorial staff of the school yearbook, the Quill; a member of the National Honors Society; and a past secretary of the Student Council.

After graduating in 1959, she went to the all-women Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, NY where a few weeks after arrival, Conwell became the class president. Her major was French and she listed her loves as New York City and theater. In the summer of 1961, she spent seven weeks in the République du Congo with the Operation-Crossroads Africa Project—helping to build a youth center in the small village of Mouyundzi, and this is where she first met Douglas Collins, the man who would become her first husband.

A watershed in her life occurred in the spring of 1962 when two leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Charles Sherrod and Charles Jones, visited her campus. Arriving on campus with Sherrod and Jones was Peggy Dammond (now Preacely) from Harlem.

That summer the two friends traveled with other college students to work as field workers to register black voters in Lee County as part of SNCC’s Southwest Georgia Project. They were lucky to be staying with Mama Dolly Raines, who was considered the mother of the Albany Movement and worked closely with Charles Sherrod.

Collins, along with Dammond, Penny Patch and Prathia Hall canvassed door-to-door in Terrell County, urging black residents to register to vote and taking them to the county courthouse to help them do so. They also spoke at the county churches to urge others to do the same. As part of the Albany Movement, Conwell was arrested twice–once for refusing to stop praying with six others on the steps of City Hall. The day after she and others spoke at the Mount Olive Church in Terrell County in Georgia, white supremacists burned the church to the ground.

Kathleen’s first two days under arrest were spent in the Albany jail. ‘The women’s cell overlooked an open latrine. It was hot, ventilation was poor and there were 10 of us in a cell meant to hold four. The place was crawling with vermin.’ Kathleen was transferred to the Leesburg Stockade, about 11 miles from Albany. Kathleen said that in Leesburg 59 women were crowded in a cell 25 feet long and 10 feet wide and given two meals a day. Breakfast consisted of chicory and cold grits. Supper consisted of one fried egg, black-eye peas, corn bread and water. They were allowed no books. Their time was spent singing freedom songs and hymns, praying and playing cards with a smuggled-in deck... They used part of the time to teach other prisoners about civil rights and voting registration."

—The Jersey Journal, September 1962

Conwell returned to Jersey City in September of 1962 and spoke to an overflowing crowd of 700 at the Mt. Pisgah A.M.E. Church, urging the congregation (according to the September 25, 1962 Hudson Dispatch) “to spurn ‘hatred...and learn to love’ those who oppress them, both in the south as well as the north because ‘we believe in God...who will open the doors and break down the walls of segregation.’”

She told the congregation about a white student who was arrested with them and offered a deal by the deputy sheriff to be let out on bail. When he refused to desert his friends the town sheriff threw the young man into a cell with some of the town’s “riff-raff,” shouting: “Here’s a ni--er-lover—let him have it!” The boy sustained a broken jaw and three broken ribs, but later simply told Conwell that it was just “one of our occupational hazards.” She spoke about a second boy who had been chased by a truck and across a field before he was being beaten unmercifully.

The Jersey Journal praised Conwell’s eloquence and oratory, and reported that the congregation was brought to tears by “a slip of a girl whose vocation is not the pulpit, but maybe it should be.” Conwell “tearfully appealed for justice for her race, appealed to the heart of humanity for the recognition of the Negro as a child of God, as a man with a bleeding heart in a world that hasn’t cared.”

In 2002, civil rights activist Ralph Allen recalled hearing Collins use the words “I have a dream” in the prayer service that day. Although there is no established origin for the phrase made famous by Reverend Martin Luther King — he first used it in a speech in November of that year — historians cite three possible sources. One of them is Kathleen Collins.

During her college years, Conwell wrote thoughtful editorials for the school paper (The Skidmore News), including a history of SNCC and think pieces on Africa, Red China, discrimination, freedom of the press and the United Nations. They were all about creating a better world — one that she was already trying to change with little regard for her personal safety. Conwell graduated from Skidmore in 1963 with a BA in Philosophy and Religion.

After graduating Skidmore, Kathleen taught high school French in Newton, MA and attended graduate school at Harvard at night. In 1965, she won a John Whitney Hay scholarship, enabling her to pursue her masters in French literature through the Middlebury program at the Sorbonne in Paris. She took a course at there on the adaptation of literature into film, which ignited her interest in cinema.

In 1966, after getting her degree, she returned to the US and joined NET, the New York City public broadcasting network, working on such programs as American Dream Machine, The Fifty-First State and Black Journal. She trained under John Carter, one of the first black editors to join the union. He thought Kathleen had real talent and he helped her get her union card in an astonishing three years. After NET, she worked as an editor for the BBC, Craven Films, Belafonte Enterprises, Bill Jersey Productions, William Greaves Productions, and the United States Information Agency.

On her own, Kathleen began writing stories. She wrote her first screenplay in 1971, but later remembered, "Nobody would give any money to a black woman to direct a film. It was probably the most discouraging time of my life.”

By 1974, she had married and divorced Douglas Collins; had two children, Nina and Emilio; and was working as a professor of film history and screenwriting at the City College of New York. In the following two years she also worked as assistant director for the Broadway musicals “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” (Gilbert Moses directing) and “The Wiz” (Geoffrey Holder) as well as on Lincoln Center’s “Black Picture Show,” which was written and directed by Bill Gunn. In the fall of 1976, Joseph Papp directed a workshop of Collins’s and composer Michael D. Minard’s musical “Portrait of Katherine” at the Public Theatre. This play was later performed as “Almost Music.”

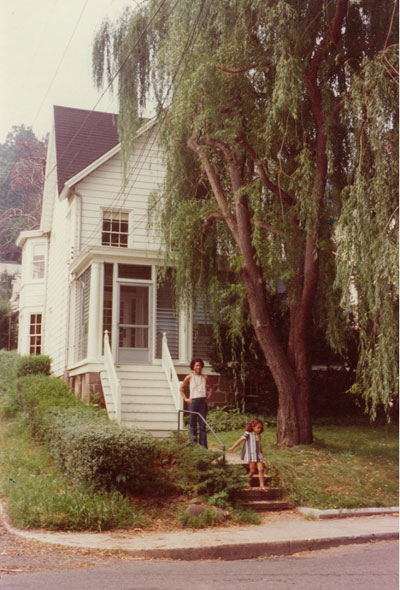

One of her City College students, Ronald K. Gray, encouraged her to direct her own films. Collins was now living now in Piermont, NY (besides her work at CCNY, she was also teaching French at the Green Meadow School in Spring Valley), and she chose to adapt a short story collection, The Cruz Chronicles by her friend and nearby South Nyack resident, Henry H. Roth, for her first film. It was very much a local affair. The composer for the film who worked with her on “Almost Music,” Michael D. Minard, was sharing Roth’s house at the time and associate producer Eleanor Charles came from Spring Valley. Charles also scouted locations for the shoot in nearby areas of Rockland County.

The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy started with an initial investment of a mere $5,000 from friends plus a line of credit from DuArt Labs. The 1980 film, which chronicled the adventures of three Puerto Rican brothers scraping by while contending with the ghost of their dead father, eventually won First Prize at the prestigious Sinking Creek Film Festival. Collins’s decision to make a film on a Latino subject bothered some critics, but she felt she needed some distance from her own world for her first film. When asked later in life if she thought that black and women filmmakers had an obligation to address issues relating to race and gender, she replied, “I think you have an even greater obligation to deal with your own obsessions.” Talking about the experience of making The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy, she recalled, “It was a terribly hard film. It was awful doing a movie for $5,000. It was like going down a terribly long tunnel... But we did it. And we did it because Ronald [Gray] and I were really very good partners and have remained very good partners. We both have an incredible tenacity.”

The film was shot in 1979 in Rockland County, NY, with most locations centered in the riverside town of Piermont. The brothers’ run-down house still stands (now in much better condition) on the dead-end part of Paradise Avenue, a quiet lane that runs parallel to the winding Sparkill Creek, which also appears in the film. Collins wasn’t the only one who found her hometown of Piermont cinematically interesting — in 1983 Woody Allen used it as his Depression-era backdrop for The Purple Rose of Cairo.

The cast was comprised of local New York actors known mostly for their theater work. The Cruz brothers were played by Randy Ruiz, who had been in Elizabeth Swados’s Broadway musical, “Runaways;” Lionel Pina, who had previously appeared in Dog Day Afternoon, Marathon Man and a PBS series, Watch Your Mouth; and Jose Machado, who was in The Goodbye Girl and Robert Young’s movie Short Eyes. Jose Aybar, of nearby Haverstraw, sang the film’s theme song, “Somos Hermanos.” The only non-local exception was Californian Sylvia Field, who portrayed Miss Malloy. Even Field had a local connection — her son-in-law Mike Kellin was Henry H. Roth’s South Nyack neighbor. Although Field’s long film career dated back to 1928, audiences knew her best as Mrs. Wilson on the Dennis the Menace television series.

Collins, who was the recipient of writing fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, and in 1982 and 1983 a finalist for the Susan Blackburn International Prize for Playwriting, always considered herself a writer first. But it was a filmmaker, Haile Gerima, who introduced Collins to the author who most influenced her work — Lorraine Hansberry, the playwright of “A Raisin in the Sun.”

My first commitment is actually to writing and the form that that takes is really largely dependent on what’s on my mind. I’ve been writing now for almost 20 years... So when I first start something, I always go to the typewriter... The older I get, I have this feeling of being very connected with Lorraine Hansberry. I’ve never found another black writer who I felt was asking the same questions I was asking until I started reading her work... And the fact that she was able to encompass this wide range of experience, from Jewish intellectuals to black middle class to Africa—she had a really incredible sense of life that fascinates me. That anything in life was accessible for her to write about... The thing that interests me about her, probably more than anyone else, is her illness. She died very young, and she died basically eaten up. My theory is that she was not only way ahead of her time, but that success came at a time when she was not able to absorb it without its destructive elements eating her body up. — Interview with David Nicholson, Black Film Review, Winter 1988/89 Hansberry must have been very much on Collins’ mind because the filmmaker fell ill after completing The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy.

My basic premise is that illness is psychic disconnection of some kind. And I had a period of time when I was ill. I still have to struggle with it. The nature of illness and female success and the capacity of the female to acknowledge its own intelligence is a subject that interests me a lot... I had just finished a first movie, and knew that I had it, knew that I had the talent. Knew that my own creative power was finally surfacing, that all the years of working quietly, and quite alone, were beginning to pay off. It was basically a four-year cycle, which I’m just coming out of. When I did The Cruz Brothers, I knew I had something. It was 1979 and I was 37. It probably takes that long to mature...

— Interview with David Nicholson, Black Film Review, Winter 1988/89

Collins’s next film, Losing Ground, followed in 1982 and starred Seret Scott, Bill Gunn, and Duane Jones. (Her screenplay, which differs in some significant ways from the film, is included in Screenplays of the African-American Experience, 1991, edited by Phyllis Rauch Klotman.) Collins began filming having initially raised $25,000 of the final production cost of $125,000.

A comedic drama, Losing Ground was one of the very first fictional features by an African-American woman filmmaker. It tells the story of Sara Rogers, a brilliant and beautiful black philosophy professor (played by Collins’s close friend Seret Scott), and Victor, her outgoing artist husband, at a marital crossroad. When Victor rents a summer country house to celebrate a museum sale, the couple’s summer idyll quickly goes awry. While Victor woos and paints Celia, a lovely local Hispanic girl, Sara pursues her research into the religious and philosophical meaning of ecstatic abandon, and her search to find it in her own life. When she agrees to perform in a student’s thesis film, Sara is charmed by her costar, the charming uncle of the filmmaker. The plot of the student film, a retelling of the song “Frankie and Johnny” mirrors the troubles in Sara’s own marriage. When the crisis in her marriage erupts, Sara’s submerged anger and resentment come out realistically, honestly, and explosively. The film ends with no easy resolutions.

Losing Ground won First Prize at the Figueroa International Film Festival in Portugal and garnered some international acclaim but received little notice in the United States.

During those years of activity in the early 1980s, Collins also produced equally remarkable dramas. Her two most famous plays were part of The Women’s Project. “In the Midnight Hour” (1980) portrayed a middle-class black family at the outset of the civil rights movement, and was directed by Billie Allen, who played the mother in Losing Ground. “The Brothers” (1982) was published in Margaret B. Wilkerson’s Nine Plays by Black Women (1986) and named one of the twelve outstanding plays of the season by the Theatre Communications Group. It delineates the impact of racism and sexism on a middle-class black family from 1948 to 1968 as articulated by six intelligent, witty, and strikingly different women. The brothers themselves, though never seen, are vibrant presences through the women’s remarks. “The Brothers” was produced at the American Place Theater and featured many familiar faces from Losing Ground. Billie Allen directed, the music was once again by Michael D. Minard, Duane Jones performed three roles (he was also Assistant Stage Manager), and Seret Scott was also in the cast.

Themes frequently explored in Collins’s work are issues of marital malaise, male dominance and impotence, and freedom of expression and intellectual pursuit. Her protagonists are cited as “typically self-reflective women who move from a state of subjugation to empowerment.”

In 1983, Collins reconnected with Alfred Prettyman, whom she had known twenty years earlier in her SNCC days. They married four years later at her home in Nyack, NY with only family in attendance. Prettyman, a philosopher and publisher, was also the head of the Society for the Study of Africana Philosophy (SSAP), based in New York City. SSAP is a forum for the discussion of philosophical ideas. It was established to provide a network of support for young African American philosophers and other intellectuals and to bring alternative voices to re-center the predominantly Eurocentric focus of and lack of diversity in most academic philosophy departments.

One week after their marriage, she learned that she had metastasized breast cancer. Collins kept this information to herself over the next year. She did not even tell her children of her illness until it was impossible to conceal it any longer.

At the time of her death in 1988, Collins left behind many projects including the screenplay, “Conversations with Julie;” a film musical she wrote with Michael D. Minard entitled “A Summer Diary;” her sixth stage play, “Waiting for Jane;” and an unfinished draft of her first novel, Lollie: A Suburban Tale. She was just 46 years old. One of the first black American women to produce a feature-length film, she is considered to have “changed the face and content of the black womanist film.” Collins’s work is significant in that it conveys images of people of color, particularly women, in ways that even now are rarely seen in popular culture. She challenged stereotypes and explored the interlocking oppressions of gender, race, and class.